A story of netsuke, Viennese bankers, loss and transformation....

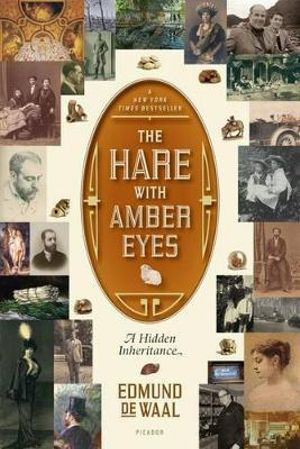

Last week, as I was fossicking through the 'Book Grocer', for my weekly reading 'treat', The Hare with Amber Eyes by Edmund De Waal, caught my eye. A quick glance at the back cover, threw back two words which were new to me - netsuke and 'vitrine'. Both sounded vaguely challenging, but the photo montage on the cover was captivating (yes that is a strange adjective for a book cover), but I am a sucker for sepia and Edwardian photos and there were many. Finally, there was the dim recollection of having chanced upon a recommendation somewhere, so I bought it. In doing so, I have given myself the gift of one of the best books I have read in a long time...

A quick Google search reminded me that De Waal's book had made The Economist's 'Books of the Year' list in 2010, where it was described as "A magical study of how objects get handled, used and handed on, by a British ceramicist who inherited a vitrine of 264 Japanese netsuke, all that was left of the Ephrussi banking dynasty from whom he is descended." The book, in essence is about a collection of miniature Japanese sculptures (netsuke) which became a prompt for the Ephrussi's and ultimately De Waal's own story.

Netsuke, were invented in 17th century Japan and had a practical purpose, to hold up containers hung from the sashes of men's kimonos. The containers, known as sagemono, contained personal belongings including pipes, tobacco, money, seals, medicine, etc. They were hung by cords from the sashes that were used to fasten kimonos and secured at the cord with a carved, button-like toggle called a netsuke which were often beautifully crafted objects of art in themselves, made of ivory, boxwood, clay, lacquer, porcelain or cane. There are different categories of netsuke ranging from compact three-dimensional figures between one and three inches high, fashioned like mice, hare and miniature animal groups and people, to buttons, masks and 'trick' mechanisms with moving parts.

De Waal, a British ceramicist, art historian, curator and author, inherited the collection which has been in his family, the Ephrussi since 1871. They were once a stupendously wealthy European Jewish banking dynasty, peers of the Rothschilds, and had owned extensive properties in Odessa, Vienna and Paris prior to the Second World War. Most of their possessions, including priceless works of art, were confiscated by the Nazis in 1938, but the netsuke, hidden away inside a mattress by Anna, a loyal maid, remained in the family. By the time De Waal saw them, they were back in Japan, this time, stored in a vitrine or glass paneled cabinet, specially designed for displaying objects d'art.

The story could easily have descended into a saga of loss and "might have been"s - maudlin and nostalgic, even bitter or worse, but instead, De Waal managed to change it into something entirely unexpected: A celebration of a past hewn out of hard work, vision, enterprise, love of beauty and tragic loss, to the fashioning of a present infused with insight, compassion, tolerance and talent. Don't let my overuse of adjectives put you off - somewhere behind them is an inspirational story. A story of how it is possible to transform the horrors and losses of the past into a future full of possibility, hope and potential gifts.

Well if you want to know more, you have to read the book your self. To whet your appetite, here is a link to De Waal's speech at the Palais De Ephrussi. in Vienna, which was once his ancestral home and the place where his family first housed the netsuke collection. De Waal went on to incorporate vitrines into his own ceramics practice and to allow his netsuke collection to inspire him to examine the meaning of inheritance, loss, diaspora, identity and creativity in his own life and ultimately in that of contemporary society. A gentle, entertaining parable for our times, this book and its aftermath, reminds us of the trans-formative power of family stories and how they can help us re-frame our pasts into empowering futures, not just for ourselves, but for everyone.

A quick Google search reminded me that De Waal's book had made The Economist's 'Books of the Year' list in 2010, where it was described as "A magical study of how objects get handled, used and handed on, by a British ceramicist who inherited a vitrine of 264 Japanese netsuke, all that was left of the Ephrussi banking dynasty from whom he is descended." The book, in essence is about a collection of miniature Japanese sculptures (netsuke) which became a prompt for the Ephrussi's and ultimately De Waal's own story.

Netsuke, were invented in 17th century Japan and had a practical purpose, to hold up containers hung from the sashes of men's kimonos. The containers, known as sagemono, contained personal belongings including pipes, tobacco, money, seals, medicine, etc. They were hung by cords from the sashes that were used to fasten kimonos and secured at the cord with a carved, button-like toggle called a netsuke which were often beautifully crafted objects of art in themselves, made of ivory, boxwood, clay, lacquer, porcelain or cane. There are different categories of netsuke ranging from compact three-dimensional figures between one and three inches high, fashioned like mice, hare and miniature animal groups and people, to buttons, masks and 'trick' mechanisms with moving parts.

|

| A 'trick' netsuke - Image Courtesy Wikipedia Commons |

The story could easily have descended into a saga of loss and "might have been"s - maudlin and nostalgic, even bitter or worse, but instead, De Waal managed to change it into something entirely unexpected: A celebration of a past hewn out of hard work, vision, enterprise, love of beauty and tragic loss, to the fashioning of a present infused with insight, compassion, tolerance and talent. Don't let my overuse of adjectives put you off - somewhere behind them is an inspirational story. A story of how it is possible to transform the horrors and losses of the past into a future full of possibility, hope and potential gifts.

Well if you want to know more, you have to read the book your self. To whet your appetite, here is a link to De Waal's speech at the Palais De Ephrussi. in Vienna, which was once his ancestral home and the place where his family first housed the netsuke collection. De Waal went on to incorporate vitrines into his own ceramics practice and to allow his netsuke collection to inspire him to examine the meaning of inheritance, loss, diaspora, identity and creativity in his own life and ultimately in that of contemporary society. A gentle, entertaining parable for our times, this book and its aftermath, reminds us of the trans-formative power of family stories and how they can help us re-frame our pasts into empowering futures, not just for ourselves, but for everyone.

Thank you very much Ruma. Cheers - Gillian

ReplyDelete